- recipe_the-future-scientists-familiar-scents_en

- recipe_the-tale-of-water-in-my-house_en

- recipe_a-circular-water-case_en

Downloads:

The tactic of water testing reveals signs of change—but never all at once. A reading of salinity, pH, or heavy metals is only a fragment of a larger puzzle. Often framed as a sterile diagnostic, testing becomes a shared method of sensing when it includes the bodies, memories, and knowledge of those who live with water. Testing is not just for experts; it invites participation. It asks: What has changed? Who feels it first? What do the numbers miss? Incomplete yet urgent, the puzzle resists simple answers—asking us instead to assemble, interpret, and act collectively.

Since 2021, Labtek Apung has conducted ongoing research in Muara Gembong, a coastal district in Java, Indonesia’s most densely populated island. This area is a hotspot of coastal erosion, driven by extractive fish-farming and the disappearance of mangroves. It also sits at the estuary of the Citarum River, one of the region’s most significant and polluted waterways.

Water testing began as a way to detect the appearance of pollutants. But pollution is more than a reading on a test strip. It circulates, it transforms lives. The most meaningful findings emerged not from the data alone, but through recognizing non-human signals and actors in the environment, engaging local residents as co-researchers, rethinking sensing as a mode of measuring, and translating between expert systems and lived knowledge.

In São Paulo, the springs of the Saracura River in Bixiga are well known, especially those flowing from the Grota do Bixiga. In daily life, these springs—particularly where the water bursts most strongly—are still used and tended by the local community. This regular, embodied engagement foreshadows a political exercise of the commons. Here, water itself asserts presence, not only as resource but as political agent.

This technopolitical gesture expands the very meaning of democracy: inviting science and the biocultural knowledge of the neighborhood into the political arena. As the video accompanying this work suggests, even though we share one planet, many worlds live upon it.

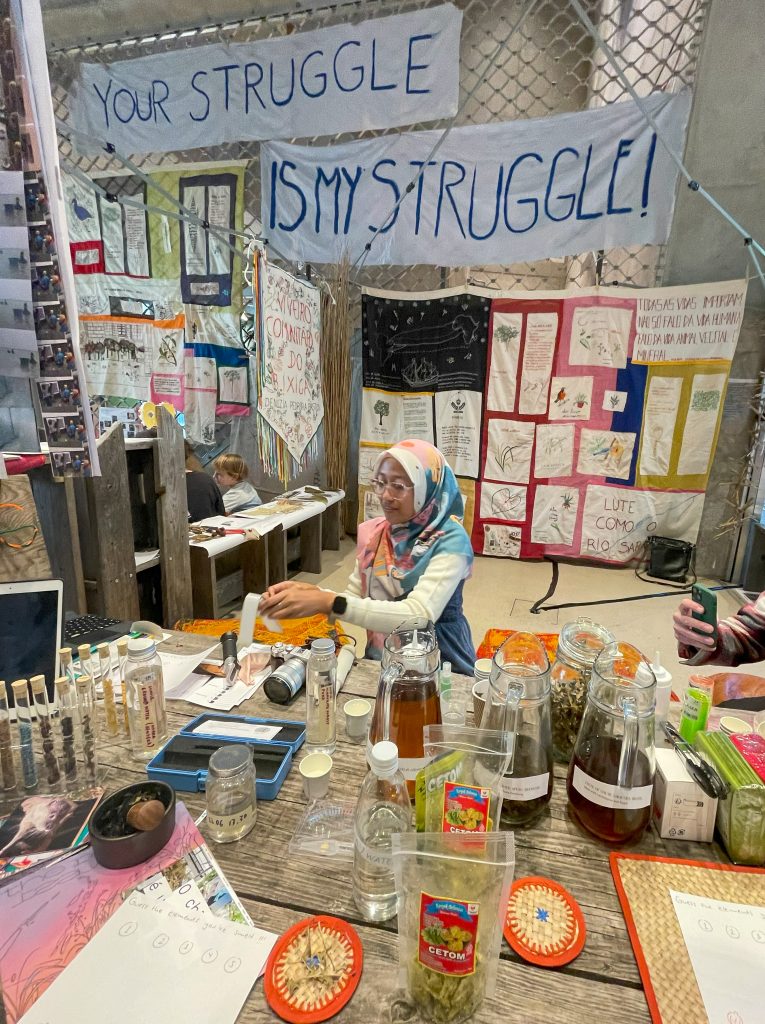

On October 12, 2023, Children’s Day in Brazil, we improvised a “Water Tasting Bar,” inspired by Floating University Berlin. We harvested herbs in the community garden in Bixiga and the participants of the workshop created their own drinks we then offered to people in the street.

Later, on October 26, 2024, Labtek Apung hosted the Cozy Lab workshop as part of Designing with the Planet at the Warung Space in Spore Initiative Gallery. The space became a self-organised infrastructure to share practical knowledge about low-tech water quality testing, counter-map colonial legacies alongside Ground Atlas and Salve Saracura, and explore multispecies cohabitation practices with Floating University.

At Cozy Lab, participants learned how to conduct simple environmental tests in everyday settings. Novita and Mia collected leaves from trees around the venue, introducing modest lab methods to detect salinity, an indicator of contamination. The workshop highlighted elements in water linked to human activities, showing that pollution sensing can be both accessible and empowering.

Visitors were invited to engage with evidence from water and river species from Jakarta, Berlin, and São Paulo. In the etalase (shop window), they explored images of our struggles presented in rencengan (sachet strip) format. At the meja lesehan (low bar tables), people carried out experiments, exchanged stories, and imagined new solidarities across rivers, cities, and worlds.

Water quality has been a recurring focus at Floating University, explored through multiple phases of testing and public engagement. As part of the project WEB – Water, Earth, and Biodiversity, scientists Katherine Ball and Martina Kolarek from the Floating team collected water and soil samples from the rainwater retention basin. These samples were analyzed in a laboratory, and the results were later shared online and discussed in public sessions, opening up scientific data to broader, collective interpretation. After this initial phase, regular testing paused for several years due to limited time and resources.

In spring 2025, a new chapter began when Ute responded to an open call from the Wasserkompetenzzentrum Berlin, part of an EU-funded initiative. The call invited Berlin residents to become “lake godparents”, taking on the care of local water bodies through simple, regular water quality testing. Ute became the godmother of both the rainwater retention basin at Floating University and the small lake in Görlitzer Park.

In July 2025, the environmental organization BUND (coordinator of the Water Network Berlin) visited Floating to carry out additional tests. These tests use basic kits, commonly found in aquarium or angler shops, which are affordable, accessible, and easy to use. This approach makes water monitoring a collective, ongoing effort bringing citizen science into everyday practice.